|

|

|

|

Why do we so often find ourselves stuck when writing or generating ideas…and how might we get unstuck and move forward?

In 1979 poet and educator Betty Sue Flowers wrote a short, compelling essay titled Madman, Architect, Carpenter, Judge: Roles and the Writing Process. [1] Flowers, an emeritus professor of English at the University of Texas and the former director of the LBJ Presidential Library, was seeking to help writers get unstuck, but I find her framework applicable to any context where we're trying to tap into our creative powers and make something out of nothing (or just make something better.) Flowers believes the creative process bogs down when two of our primary personas clash:

What happens when you get stuck is that two competing energies are locked horn to horn, pushing against each other. One is the energy of what I'll call your 'madman.' He is full of ideas, writes crazily and perhaps rather sloppily, gets carried away by enthusiasm or anger, and if really let loose, could turn out ten pages an hour.

The second is a kind of critical energy–what I'll call the 'judge.' He's been educated and knows a sentence fragment when he sees one. He peers over your shoulder and says, 'That's trash!' with such authority that the madman loses his crazy confidence and shrivels up.

Flowers' solution is to introduce two intermediate personas who hold the judge at bay while refining the madman's raw output, first the 'architect' and then the 'carpenter':

[T]he trick to not getting stuck involves separating the energies. If you let the judge with his intimidating carping come too close to the madman and his playful, creative energies, the ideas which form the basis for your writing will never have a chance to surface. But you can't simply throw out the judge. The subjective personal outpourings of your madman must be balanced by the objective, impersonal vision of the educated critic within you…

So start by promising your judge that you'll get around to asking his opinion, but not now. And then let the madman energy flow. Find what interests you in the topic, the question or emotion that it raises in you, and respond as you might to a friend-or an enemy. Talk on paper, page after page, and don't stop to judge or correct sentences. Then, after a set amount of time, perhaps, stop and gather the paper up and wait a day.

The next morning, ask your 'architect' to enter. She will read the wild scribblings saved from the night before and pick out maybe a tenth of the jottings as relevant or interesting. (You can see immediately that the architect is not sentimental about what the madman wrote; she is not going to save every crumb for posterity.) Her job is simply to select large chunks of material and to arrange them in a pattern that might form an argument. The thinking here is large, organizational, paragraph level thinking-the architect doesn't worry about sentence structure.

No, the sentence structure is left for the 'carpenter' who enters after the essay has been hewn into large chunks of related ideas. The carpenter nails these ideas together in a logical sequence, making sure each sentence is clearly written, contributes to the argument of the paragraph, and leads logically and gracefully to the next sentence. When the carpenter finishes, the essay should be smooth and watertight.

And then the judge comes around to inspect. Punctuation, spelling, grammar, tone-all the details which result in a polished essay become important only in this last stage. These details are not the concern of the madman who's come up with them, or the architect who's organized them, or the carpenter who's nailed the ideas together, sentence by sentence. Save details for the judge.

I love the distinction Flowers draws between the different phases of the creative process and the order in which they should proceed:

1. Generate: Unleash your energies and generate as much raw material as you can.

2. Organize: Select the most promising chunks and organize them at the conceptual level.

3. Refine: Drop down a level and refine your work's overall logic, clarity, and flow.

4. Polish: Get down to details and final polishing only after you've progressed through the first three phases.

My own worst tendency is not just to skip steps 2 and 3 but to collapse steps 1 and 4 into a single process, sweating the details even as I'm coming up with ideas. It's not simply laziness–although sometimes I am looking to save time–but a failure to recognize that the creative process involves radically different tasks at each stage.

Those different tasks require not only different mindsets but also different approaches to the work. They may look similar at a superficial level, because they all involve me sitting at my laptop or hovering over a pad, but they're really not. And it's useful for me to be clear on what work needs to be done AND on the mindset and approach that will best support that work.

For example, some work is best supported by the clarity and calm I feel early in the morning, while other work requires the expansiveness and random connections that come to me late at night. Some work can be done anywhere, while other work requires a quiet, private setting. This isn't to say that I have a set of heuristics that determine what work I should be doing at any given moment, but I'm starting to pay more attention to these factors, and I do feel more productive when there's greater alignment among them.

Finally, it's worth noting that following Flowers' advice requires discipline. Not only do I need to dedicate sufficient time to each of the 4 phases (and to periods of rest and reflection in between them), but I also need to be prepared to "Murder my darlings," in Arthur Quiller-Couch's colorful phrase–to toss out ideas and passages that may strike me as brilliant but that are distracting me from focusing on my primary objective. I'm reminded of Steve Jobs' dictum, "Focus is about saying no…You've got to say no, no, no."

Thanks to Betty Sue Flowers for the inspiration, and thanks to Josh Rolnick and his essay My Life in Stories for first introducing me to Flowers. The American-Statesman's Brad Buchholz provides some fascinating background on Flowers in a profile that accompanied her departure as director of the LBJ library, a move prompted by her relationship with former Senator Bill Bradley–a very touching story.

Footnote: [1] Prior to the version linked above, which was posted in 1997, Flowers published the original version of her essay in 1979 in Proceedings of the Conference of College Teachers of English of Texas 44, and it was republished in 1981 in Language Arts. Thanks to Douglas Perkins.

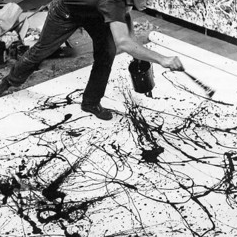

Photos: Jackson Pollock (Madman): Unknown, Mr. McKeen (Architect): Seattle Municipal Archives, Carpenter: Unknown, Judge John Caverly: Chicago Historical Society